If you have even a passing interest in film, you’ve probably heard of the Pentax 17 by now. Released last year in response to the growing nostalgia for analogue photography, it’s one of the few new film cameras to come out in the last decade—and probably the only one from a major manufacturer that isn’t Leica. Pentax took a risk, targeting Gen Z’s fascination with a world they never actually lived in by creating a half-frame camera that sits somewhere between fully manual and fully automatic.

But who is it for?

Rather than catering to professionals, serious enthusiasts, or wealthy collectors looking for flashy trinkets, this camera is clearly aimed at hipsters. You can tell just by the fact that its designer, Takeo Suzuki—who goes by TKO—sports a waistcoat and flat cap. But is this camera a technical knockout? Well, I had my doubts, but I bought one as a Christmas present to myself. Why? Because I deserve it. Okay, also because my wife saw it, immediately wanted one, and who am I to argue?

Credit where it’s due—Pentax took a bold step releasing this niche product, especially at around 800 Australian dollars. I wasn’t planning on buying it until my wife convinced me that it would make me happier, healthier, and an all-around better human being. Has it changed my life? Not really. Let’s be honest—I don’t need another camera. But I do love half-frame cameras, and my old Canon Demi is getting unreliable. The Pentax 17, on the other hand, is brand new, fully functional, and—unlike my usual vintage finds—doesn’t smell like leather, tobacco, and urine. Don’t worry, I’ll add that patina over time.

This camera is supposed to be fun. Half-frame means I don’t have to worry as much about film costs, and the resolution is decent for most uses. Unlike Pentax’s 90s-era fully automatic point-and-shoots, this one puts some control back in my hands. Some, but not all. You have to focus manually using an icon-based system (flowers, people, mountains, and—of course—your dinner, because Instagram). You also have to wind the film on manually, which was about the hardest work I did all summer.

Early frames

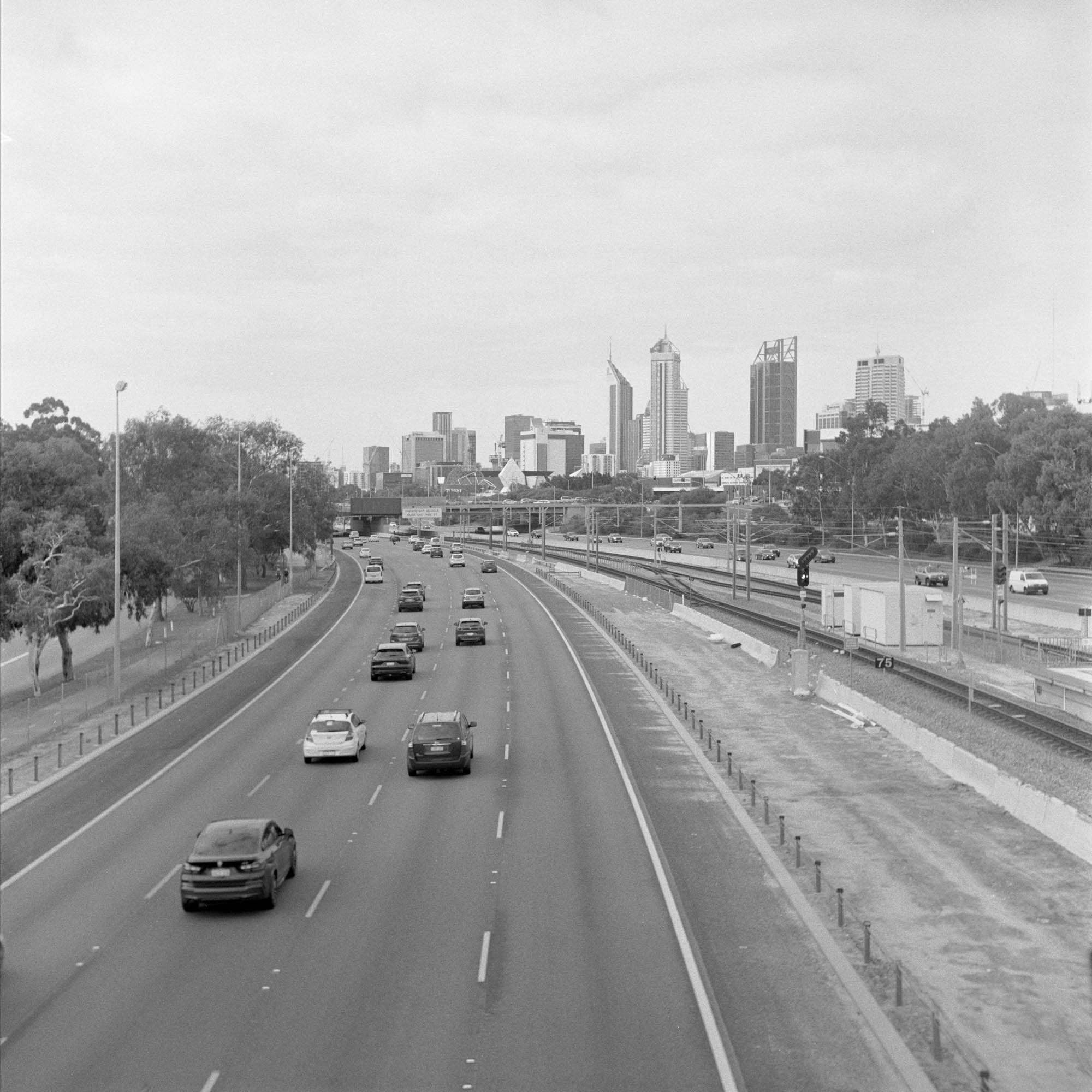

Of course, it’s not all fun and games. I took my Pentax 17 and some Ilford HP5 and set out to capture some of the urban decay of tired shopping malls. The results? Nothing spectacular, but it did at least provide a monochromatic record of decline. But I know that’s not what you’re here for—you want your decrepitude in full color. So, I loaded up some Fuji 400 and headed to my home away from home, Leeman, for post-Christmas dog walks on the beach.

Speaking of which, my groodle puppy, Juni, has had plenty of exposure on film this summer. If you’ve been following along, yes, it’s the same dog—just three times bigger. We’re considering renaming her Ginger Monster. Capturing a fast-moving ball of auburn fur with a half-frame camera? Tricky, but fun.

Camera quirks

Now, about those exposure modes. They’re confusing. The dial is color-coded: white for non-flash modes, yellow for flash-based ones, and—just to mess with you—a blue auto mode that isn’t actually fully automatic. It basically turns your expensive camera into a $20 disposable. What focus distance? What aperture? What shutter speed? Who knows? I don’t use it. Instead, I stick to P mode, though I still don’t really know what it does. The biggest issue? The dial is way too easy to knock out of place, which led to some overexposed outdoor shots and underexposed indoor ones before I realized I’d accidentally switched to Bulb mode while winding on.

After some trial and error, I learned a few things. One: get your finger out of the way when shooting macro. Two: framing in a viewfinder camera is always a challenge, but the Pentax 17’s clear viewfinder and close-up frame lines help. Three: for general shooting, the 3m focus setting is usually good enough, though I did cheat and use an iPhone app to double-check distances.

I still haven’t touched auto mode—it gives me anxiety. With half-frame, I like to have two exposed rolls ready before developing to save time and chemicals. So, to make things more difficult for myself, I loaded up a roll of OneShot film next. Why? Because it was cheap. The results? Let’s just say OneShot probably isn’t ideal for a bright Perth summer—or for this camera. The muted colors and heavy grain didn’t do me any favors. The Fuji 400 shots fared better, and while nothing groundbreaking, I did get a few fun summer snapshots.

So, what’s the verdict? This isn’t a spectacular camera. It has its quirks—no self-timer, confusing exposure modes, and some incredibly bright blinking LEDs that don’t provide focus confirmation (because it’s manual focus). Plus, the electronic focus system introduces a slight shutter lag, which is odd for a manual-focus camera. The design is an eclectic mash-up of different Pentax and Ricoh cameras, with an Olympus Pen-style viewfinder and a winding lever that feels straight out of a Pentax 110. It’s a Frankenstein creation, and the real question is: does that make it charming or just dumb?

For me, it’s both. Plenty of YouTubers have reviewed this camera and been left scratching their heads, but that’s because it wasn’t made for high-end photographers. Honestly, it wasn’t even made for me—and I have no standards. But I love it. It’s quirky, fun, and surprisingly decent for what it is. Most of all, it’s brave and weird—just like Juni. Maybe I’m just brave and weird enough to appreciate it.