Welcome to he Pentax 120SW – a tiny do-everything-for-you point-and-shoot from right at the time where everyone started buying digital cameras. To test this camera out, I decided to explore the Gardens by the Bay area of Singapore to see if I could experience the wonder of nature.

The Wonder of Nature

I think you can probably guess that the byline of the above video is somewhat sarcastic. Gardens by the Bay is as natural as a terra-formed Mars colony, with microclimate pods nestled among metal trees, all in the shadow of Marina Bay Sands hotel.

Most of the nature exploration involved photographing the topography and the tourists that milled around the area – wildlife of sorts, I suppose, just not the normal fodder for a David Attenborough documentary.

Using a mix of Ilford HP5 and Kodak Colorplus 200, I nevertheless put on my virtual pith helmet, strapped on my scythe and cut a swathe through the metal and concrete forests of Gardens by the Bay.

About the Pentax Espio 120SW

Well what’s to say? It’s a point and shoot.

It has a 28-120mm F5.6-12.8 lens, 6 elements in 5 groups, autofocus with focus lock, and with a minimum focus of 0.5m. It’s shutter speeds are from 2-1/360s and it has a bulb mode that’s 1/2s-1min though if it came with a remote shutter, I don’t have one so I’m not sure how useful bulb really is.

Like many point-and-shoots, this one is small and it’s light. It weighs 190 gr. without battery.

That, and it’s sweet sexy looks ,are probably it’s main attractions. Apparently, other than the film door it has an aluminium body. I don’t know though. It tastes like plastic to me. I don’t know how much this cost either but it was definitely positioned at the ‘luxury’ end of Pentax’s plastic point and shoot lineup.

in 2001 it won the Technical Image Press Association’s compact camera of the year award. But given those times, it’s probably like winning ‘Best new DSLR’ in 2023 when the whole world has gone mirrorless. You do get a really pretty orange backlight on the LCD though.

One of the problems is that it’s a Pentax. This was a company that churned out compact camera models like barbecue sausages and it’s not like there was ever much cachet in owning one. I have several Pentax point-and-shoots in my cupboard. I also have a few broken ones now hidden in draws that I might sell on ebay some time labelled ‘top mint’ but with ‘please read’ asterisked and in small print.

The fact is that there were so many camera versions, some good, some bad. How do you know if you’ve got a decent one?

Well you may have already made up your mind on this one but I think to make an accurate judgement, it’s only fair that I use some of that money I’ve been saving up for my kids education and blow it on a roll of colour film. Seriously, the things I do for science. And nature … obviously. Now this was Kodak Ultramax. Still a fast film at ISO400 but still a challenge for such a small aperture zoom on a cloudy day. BUT if Livingstone could conquer Everest with nothing but a woolly bobble hat and a block of Kendal mint cake then I could take on the challenge of Marina Bay with my trusty Pentax. Actually I might have got some of that detail wrong but that’s what happens when you trust Chat GPT to write your reviews for you.

A Slow-Lensed Camera

The Pentax Espio 120SW is perhaps not the best camera out there in terms of specifications and it doesn’t have a full array of modes and features. There’s no portrait, sport mode or dedicated macro facility here. You really have very little control.

You do get 25-3200 ISO, automatic DX coding, self-timer, automatic film advance, infinity and spot AF modes.

And for what it is, it’s capable of producing great results. It can meet the resolution of film and my favourite photos show that this has a lens that can be both sharp and contrasty. I didn’t really see much flare either thanks to it’s ‘super multi coating’.

If you use it properly it delivers good results. Unfortunately I bet back in the day there are a lot of people who have used this camera and wondered why the images came out blurry. That probably comes down to the lens. It has a maximum aperture of f/5.6 at 28mm down to f/12.8 at 120mm. That makes it tighter than the proverbial cat’s anus, though I haven’t actually done that test myself and I don’t know any proverbial feline proctologists.

You only get a focus confirmation or a warning light to tell you to use flash in the viewfinder and that’s not much feedback. It’s definitely capable at 120mm as shown here but where my shots failed it was usually because I was being overly optimistic of my ability to hand hold. Even with 400ISO, a dull day in Singapore meant that telephoto and slow shutter speeds conspired to give me soft results. Don’t bother putting 100 speed film in this unless you’re prepared to shoot with the flash turned on.

But it’s Sharp

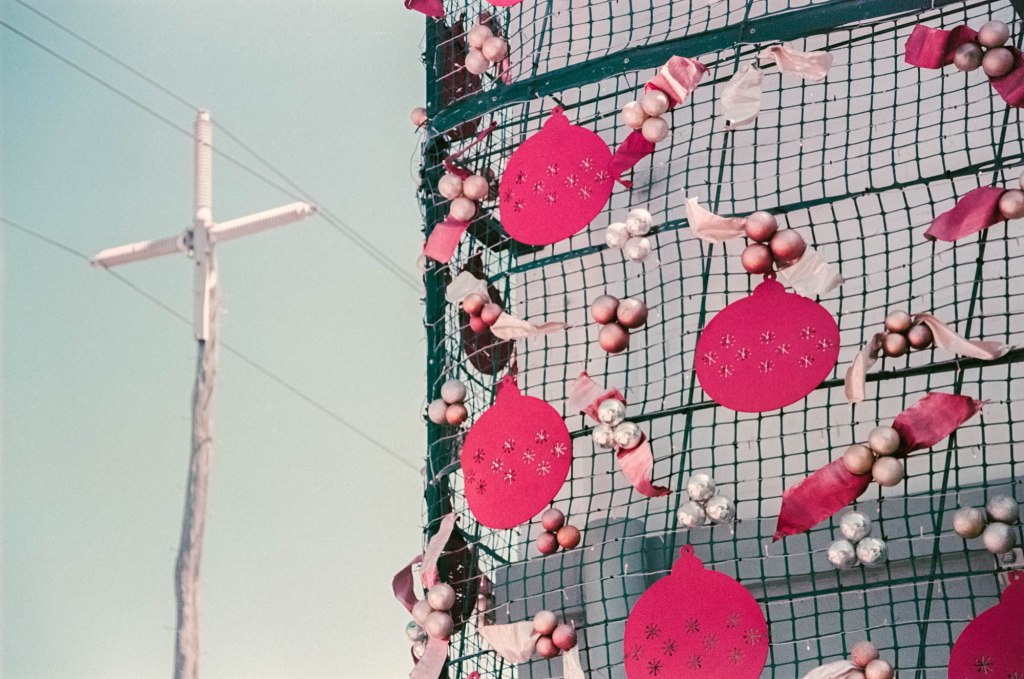

On a sunny day like we have here in Australia I still managed to get great results. Finishing the colour roll, I was able to get really vivid photos like this.

Admittedly, I might have underdeveloped a bit, which often gives colours, contrast and grain a bit of a boost but if you look here, you can see that it produces pleasing images.

As with any example of this kind of camera, though, you have to accept a certain randomness in the results it produces. There was no way I could tell the camera where to focus in this photo and while having the ability to at least spot focus fix on infinity focus is nice, the end results can be a bit unpredictable depending on the film or quality of light. I wasn’t really able to get it to produce any bokeh but that’s hardly surprising. I could get some subject separation if I shot close up and what I did see in the out of focus areas wasn’t ugly. It just wasn’t particularly distinctive.

So what’s your experience with cameras like this? Have you owned this particular model and what do you think of it? Some point and shoots can be ridiculously overpriced these days. I’m looking at you Olympus Mju II.

If you’re prepared to slum it at the ugly end of the Pentax range, though, you might find a bargain. There are definitely hidden gems out there if you are prepared to be patient.

But let me know your thoughts. From my perspective, if not the best tool for the job, this camera isn’t the worst. And like your phone it’ll give you a photographic experience that you can put in your pocket; just with this one, it’s actual film.

My advice, though, use a FAST film so you can make the most of the sharpness of the lens stopped down and give you a bit ore leeway with hand holding. Or use flash, which on these things is… ‘a look’ and who knows? Maybe one I’ll experiment with a bit more on a future review.