Today, I found myself facing a philosophical dilemma: is the Diana F+ truly a legitimate photography tool masquerading as a toy, or am I merely a tool for using a toy camera? As I embarked on this journey with the Diana, I couldn’t help but be drawn in by its quirky charm and historical associations with the goddess of the moon.

Inauspicious Origins

Despite my initial skepticism towards toy cameras, I remained open to the creative possibilities they offered. After all, some of the greatest art has been created using the most primitive of tools. Plus, snagging the Diana from a thrift store for a fraction of its original cost seemed like too good of an opportunity to pass up.

Delving into the lore of Lomography, I learned that the Diana had humble beginnings as a novelty item produced by the Great Wall Plastic Co. Yet, over time, it was embraced by a new generation of photographers seeking an alternative to the clinical perfection of digital imaging.

However, I couldn’t ignore the criticism that toy cameras often produce subpar photos due to their inherent flaws. Despite my doubts, I decided to put the Diana to the test by taking it out to a local wetland armed with Kentmere 400 medium format film.

As I loaded the film into the camera, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was about to embark on a futile endeavor. Would I be able to overcome the constraints of the Diana and capture meaningful images, or would I end up disappointed by the results?

Only time would tell as I ventured forth with the Diana in hand, ready to explore its creative potential and perhaps uncover some hidden gems amidst its quirks and imperfections.

It’s … Ok, I Guess

So, I’m here to give you my unfiltered take on this piece of plastic, based solely on my experience of shooting one roll of film with it. In short, it’s… meh.

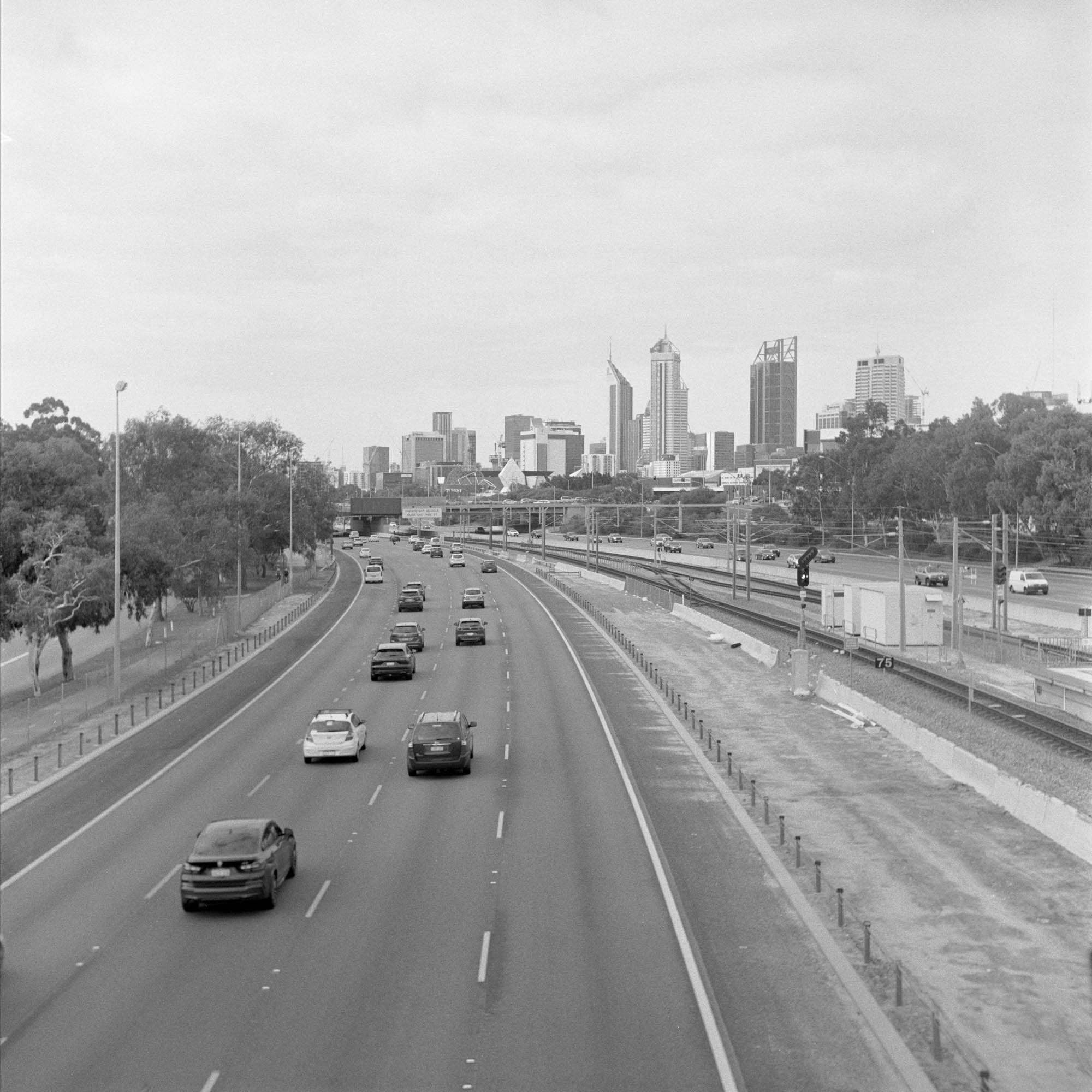

Sure, it wasn’t a complete disaster. I managed to guess the focus and exposure fairly accurately, and the negatives turned out clean with decent density and no blown highlights. Despite encountering some light leaks and strange artifacts on the film, I can’t say I was entirely disappointed.

However, when it comes to usability, the Diana F+ falls short. It’s uncomfortable to hold, and the build quality leaves much to be desired. The viewfinder is virtually useless for framing, and the shutter sounds less than inspiring.

On the upside, it’s incredibly lightweight, making it a viable option for a day trip camera. But its lack of precision and flexibility means you’re limited in your creative control. You’re essentially along for the ride, with the camera dictating the final outcome.

While some may argue that these quirks are part of the Diana’s charm, they can also be seen as limitations. The softness of the lens, inconsistency across the focal plane, and tendency for highlights to glow are all baked into the final image, for better or worse.

As for recommending this camera, I’m torn. While it may have its niche uses, particularly for street photography where spontaneity is valued over precision, I can’t help but think there are better options out there. Personally, I’d lean towards something like the Agfa Isola, which may not be much better but at least offers a sense of authenticity with its glass lens.

In the end, my experience with the Diana F+ wasn’t terrible, but it wasn’t exactly inspiring either. It’s unlikely to become my go-to camera, but it has piqued my curiosity enough to give it another chance in the future. After all, sometimes it’s worth exploring the unconventional, even if the results are a bit… unconventional themselves.